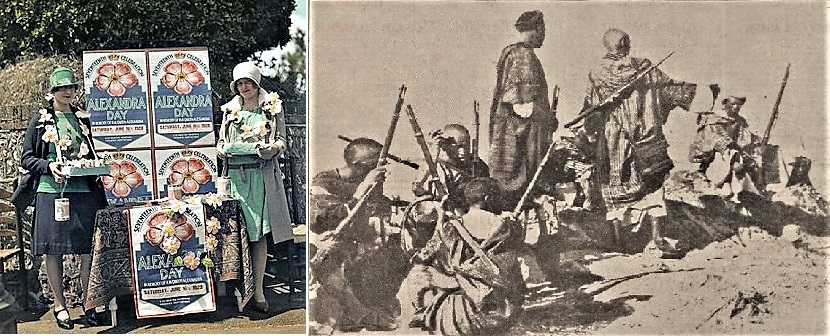

It was the 26th of June 1924, Alexandra Rose Day. One or two women were gathered outside London’s swanky Ritz Hotel selling paper flowers to raise money for charity when they were approached by a well-dressed man who handed one of them a large sum of money. “For the hospital,” he said, and walked on as he had done each Alexandra Rose Day for several years, promising to see the flower sellers again the following year.

The women told a reporter who turned up they had no idea who the generous benefactor was – “He looked like a traveller to Russia or Africa or somewhere” one of them said.

I was curious. Who was this mysterious Scotsman? I began scranning through newspapers and books and found myself transported into a world of which I knew next to nothing. Did I uncover the identity of the Scotsman? If you have a few moments to spare I’ll explain what I found out.

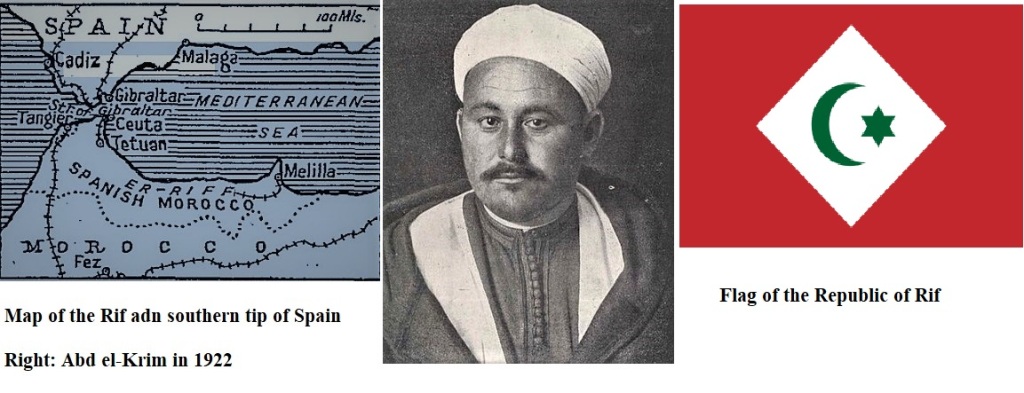

Staying in London at the time, in a west end hotel, was a Scotsman who was a technical adviser to Muhammad ibn al-Karim al-Khattabi, known as Abd el-Krim or Krim. Krim was President of the Republic of Rif – a mountainous region in northern Morocco. His people were Amazighs, a tribal group among the Berbers. Krim was one of several tribal leaders in the Rif and all were at war with the European power of Spain that held the Rif as a protectorate, having been granted it by France that colonised Morocco in 1912 and governed to the south.

Why had Spain been attracted to this inhospitable though beautiful area on the other side of the Mediterranean? Not its stunning beauty, hills sweeping up from the sea washed yellow with corn and green from banks of olive trees and everywhere giant prickly pears. No, that wasn’t it. The Rif region of Morocco was rich in easily extracted high-grade iron. And Europe couldn’t get enough cheap iron. Britain and Germany were interested. So was Spain.

Extracting the iron ore was physically damaging to the landscape and to sites that were sacred to the Berbers. It also meant the eviction of people from their traditional homelands. What did the Berbers get in return? Nothing. No compensation although some were hired to mine the ore at half the rate paid to Europeans – 4-5 pesetas per day against European wages of 7-8 pesetas. Mining was carried out under American management.

The people of the Rif resited the incursion of Europeans onto their land. But European powers still believed the world belonged to them and claimed territory they thought would be beneficial to them, if they had the power to impose themselves. So war came to the persecuted people of the Rif. A dreadful war of great cruelty and loss. The events in the Rif in the 1920s had consequences for mainland Europe over the next sixty years.

Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli was another Berber leader, of the Jebala in the north-western territory. To some he was the Desert King and to others the Rob Roy of Morocco. Raisuli’s early life seemed to promise a quiet existence. A teacher of law and theology, Raisuli’s love was books and writing. That all changed on the day he chanced upon a woman who had been assaulted by some men, apparently Europeans. Raisuli decided it was his duty to rid his country of the European Christians – the Spanish, British and Americans whom he regarded as his country’s oppressors. The Rif’s jails were filled with Rifs – put there by the Spanish colonists – beaten and denied trials Rif people were simply locked away for challenging Spain’s authority. Rifs were ordered to carry passports to move around their own country. The war that disrupted farming created Rif starvation on an immense scale. People were dropping down in the street from hunger so the Spanish authorities opened camps to contain them – picking them off the streets ‘like refuse’ to die away from the public eye. Spain complained of the cost of keeping their piece of Morocco. And yet they held it. And taxed the people. Everything sold carried a tax and people were encouraged to pay up by tax collectors armed with machine guns. Resentment against the Spanish among the Rif tribes was huge.

Raisuli used kidnap in his campaign of resistance to European colonists. In 1903 he kidnapped Walter Harris, a journalist from The Times, and exchanged him for fifteen of his Rif fighters held by the Sultan of Morocco who had submitted to France in a treaty that allowed him to retain his titles and position so becoming France’s puppet ruler in Morocco. When Spain came knocking on Morocco’s door France divied up Morocco under which France retained the southern portion and Spain was given the north. Raisuli’s men snatched a wealthy American and his son-in-law. Almost immediately British and American warships anchored in the Bay of Tangier. A deal was struck and the pair released but the guns were out for Raisuli and his people were driven deep into the mountains from where they pursued a guerrilla war against the European colonists. One of the intermediaries negotiating between the Berbers and the Europeans was a Scotsman called Kaid MacLean.

Kaid MacLean aka Sir Harry MacLean aka General Sir Harry Aubrey de Vere MacLean born in England to Scottish parents entered military service and served in Gibraltar and Tangier. Reputedly a debonaire larger-than-life character who was said to have ‘walked straight out of the pages of a novel’ MacLean came to the attention of the Sultan of Morocco who made him his counsellor, business adviser and envoy. MacLean lapped up the Moorish life except for its food. In the grand residence the Sultan provided for him MacLean employed a French chef and his musical needs were supplied by his own Italian orchestra. Classical strings can satisfy a Scotsman to a degree but a piper, himself, MacLean returned from a visit back to Britain with Aberdeen piper, John McDonald Mortimer. Soon the Sultan was won over and established his own Moroccan pipe band, attired in the MacLean tartan.

In his role as the Sultan’s envoy, MacLean was occasionally required to undertake long and arduous journeys including on horseback for up to fourteen hours a day for hundreds of miles. But he had less challenging missions. The Sultan, a shopaholic, bought a hansom cab that nobody could or would drive so MacLean took the reins and took it for a 120 mile trip to Fez. Roads in the Rif mountains were practically non-existent and mostly the cab’s wheels were removed and the cab of the hansom slung between two camels to negotiate the rocky terrain. Among the Sultan’s other purchases from Britain were several Coventry bicycles for the women in his harem to cycle. Apparently, they were none too keen.

In July 1907 the Sultan’s envoy, Kaid MacLean, was kidnapped by Raisuli’s men and held captive for seven months on demand of a ransom of £20,000 – about £200,0000 today. In the end Raisuli was only paid £5000 up front with a promise the remainder would be banked to ensure he ‘behaved’ over the next ten years. He never did get the remaining cash. In April 1922 an air bombing campaign in conjunction with a land attack by a Spanish force of 30,000 men forced his surrender. Raisuli later escaped captivity and made an uneasy alliance with Abd el-Krim to resist Spain’s grip on northern Morocco.

By this time, Kaid MacLean, Scottish soldier of fortune, was dead. He died in February 1920 at the age of 72 so he could not have been the mysterious Scottish traveller who beguiled the paper flower sellers in 1924.

In September 1924, three months after the mysterious Scot donated a large sum to charity on Alexandra Rose Day British newspapers were reporting a plot to buy weapons and recruit former officers for the Berber campaign to oust the Spanish from Morocco. Two submarines from redundant stock were sought from an armaments company in the north of England at a cost of £30,000 to use in the Straits of Gibraltar to torpedo Spanish vessels supplying their Moroccan forces with food and arms. Payment for the submarines was being put up by Abd el-Krim.

The man who had Krim’s ear was Scottish – a former officer with the Scots Greys and fluent Arabic speakers – a “daring professional soldier to whom war and adventure is life itself” and perfectly placed to recruit British men, officers, fairly recently demobbed from the Great War. The Scot offered his mercenaries 30 shillings a day plus extras dependent on “the results they obtained, together with a big gratuity when the war was over.” As well as the submarines and men, Krim’s man was authorised to purchase machine guns and aeroplanes. The Scot was confident as he knew of plenty British former pilots keen to get involved.

Despite talk of large arms the Berbers mainly depended on guerrilla tactics against Spain and later France. The Rif war reintroduced the medieval war craft of tunnelling into modern-day battle arenas – later picked up by Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong and Che Guevara.

By now Spain’s military force included the fascist Francisco Franco Bahamonde who took control of the Spanish army in Morocco. Franco and his legionnaires were notoriously savage. They delighted in mutilating Berbers and exhibiting their body parts to terrorise the local people into losing heart.

But still mighty Spain failed to overcome the Berbers of the Rif on their own and appealed to France for assistance. France provided large numbers of men under Marshal Pétain. Pétain would later become notorious for collaborating with the Nazis in Vichy France during WW2 and be convicted of treason but back in the 1920s he was a French hero who led a joint French/Spanish force against the tribes people of the Rif. France recruited sixteen American pilots to reinforce their air attacks on the Berbers in the summer of 1925. Their leader was Charley Sweeny, son of a rich industrialist who had served with the French foreign legion in WW1. Gertrude Stein criticised him for fighting on the wrong side in Morocco and for the bombing raids he led on people armed only with rifles to defend themselves with. The air action was widely condemned in the USA, especially by black groups, and 1925 became known as the year of the airplane.

Failing to make fast progress the western forces resorted to chemical warfare – attacking the Berbers with mustard gas, phosgene and diphosgene – deliberately targeting civilians shopping in markets and poisoning drinking water. This despite Spain and France having signed up to a ban on chemical and biological weapons in 1925. There was little outcry from the rest of the world over Spain’s use of chemical weapons since they weren’t used against white people.

But what of the mysterious Scotsman?

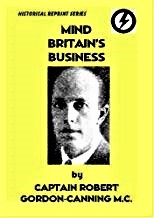

Captain Robert Gordon Canning, descendent of the Gordon’s of Cluny in Aberdeenshire, supported Arab nationalism. With strong links to Germany he organised German arms and field supplies be sent to Krim’s forces. He became Krim’s peace envoy when it was clear the Berber’s were losing the war against the combined powers of France and Spain and he left Morocco for Britain at the end of the war, in 1926. Ten years later he was best man at the wedding of the British fascist leader, Oswald Mosley, and Diana Mitford. A fellow fascist, Canning was imprisoned for three years in 1940. Canning’s German connections included an Anglo-German organisation called The Link – a pro-Nazi group particularly popular in London. The Link was banned at the outbreak of war in 1939 but reportedly resurrected in 1940 by James Bond author, Ian Fleming, to lure Rudolf Hess to Britain in 1941.

The combined forces of Spain and France and their dirty war spelled the end for the Berbers of Rif. On 26 May, 1926, Abd el-Krim surrendered to the French and was exiled. The Rif war of 1921-26 was regarded as a harbinger of the Algerian war and independence in 1963, which Krim just lived long enough to witness. Morocco achieved independence in 1956 with the submissive role of its Sultans still being much criticised by the people of the Rif. While in exile in Cairo Krim had again appealed for help for his fellow Rifs but none came and many were slaughtered by the Sultan’s forces for their continuing opposition to him. Little has changed. The people of the Rif are still persecuted – by the Moroccan authorities. They still resist. They are also still dying too young of cancer, believed to be a legacy of Spain’s illegal used of deadly chemicals in the twenties.

As for Franco – he and his legionaries gained valuable battle experience in the Rif mountains and within ten years they crossed the Med into Spain to carry out atrocities there in the Civil War of 1936 -39. Of that encounter the American journalist, Webb Miller wrote of Spain’s fascists –

I came out of Spain badly shaken by the atmosphere of blood, tears and terror, and profoundly discouraged about the future of Europe. What I saw and heard of the wide development of the use of terrorism as a definite weapon in warfare was sickening. Never in modern times has there been such a holocaust of cold-blooded slaughter of prisoners, of wounded and of helpless hostages in thousands. Terrorism of civilian populations by indiscriminate bombing from the air had largely wiped out the distinctions between combatants and non-combatants. Amongst the dead and wounded on both sides were many thousands of women and children. “We are fighting an idea,” and officer told me. “The idea is in the brain, and to kill it we have to kill the man.

(Waterford Standard 8 May 1937 )

And the Scotsman? Well I can’t say for certain. There was an Englishman, a photographer and trader called John Arnall. He was a socialist who sympathised with the Islamists of the Rif. Arnall formed the Anglo-Ottoman Society in 1914 and was a founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (but later turned against communism.) He and his wife lived for a time in Tangier and in early 1922 he visited the Rif with a plan to make money from selling mineral rights which is how he came to be involved as a spokesman for the Rifs in London, attempting to drum up support for their cause. Arnall was also a member of the Irish Socialist Republican Party and his various activities made him a target of the British Special Branch who intercepted his mail and generally kept an eye on his movements. It is believed he was killed by the Spanish in Morocco in 1924.

In 1977 a British film was made based on the Rif war of 1921-26. Called March or Die it starred Gene Hackman as a heroic white man fighting for the heroic French against the villainous Berbers. Ian Holm played el-Krim.

In 2017 a film called Iperita was made about a former Spanish pilot, guilt-ridden because of his part in the bombing of Rif villages and his return to the area to find the landscape almost obliterated and its people gone. You can watch it here –

The Scotsman outside the Ritz in 1924? I don’t know. None of the above. But there are roses still – mentioned in a contemporary song aimed at informing the young of the Rif of the cruelties of the past which have never quite left them –

We know the whole truth But we want you to confess and reveal everything Just as the pain in my heart speaks of the many torments it has endured Just as roses grow on the graves of the victims who fell from your crimes.