I can scarcely remember my grandmother’s voice – neither of my grandmothers’ voices. Like everyone I had two grannies and in my case both my grannies are now long dead for they were born into a different world, in the late 1900s. I like having that link, however tenuous, with a Scotland that’s gone forever.

My paternal Granny, Harriet (Hetty), was a strong woman, and tall as befits a McHardy from Braemar. In common with lots of folk I didn’t take much interest in either of my grannies lives but filed away in my subconscious were the odd name and incident and these aided and abetted by a few photographs and internet access to census returns, marriage, birth and death certificates have meant I’m able to better place my grannies into their family settings preceding the years I knew them. A wee bit, at least.

Harriet, let’s call her Granny 1, was born on the humble croft her parents worked on the slopes of Morrone, a hill behind Braemar. A bit lower than a Munro, Morrone is a Corbett, which means it’s between 2,500 ft and 3,000ft – an unlikely place to try to farm but somehow a community of five households did just that and they called their wee fermtoun, Tomintoul. This is a different Tomintoul from the well-known village of that name. The McHardys worked 7 acres of this the most elevated cultivated land in the whole of Scotland so it must have surprised a few people that in 1864 Braemar’s Tomintoul had the unlikely distinction of producing the country’s biggest golden yellow turnip – thirty-three inches in circumference and weighing in at a whopping 14 lbs – some achievement for land tilled from under heather, trees and boulders though as far as I know it had nothing to do with my family. For the area to sustain five families would have taken immense effort in clearing a stretch of the hillside of its heather, trees and boulders and neutralising its acid soil – they did this with lime produced from limestone in communal lime kilns. Life on Morrone would have been idyllic in spring, summer and autumn but a mighty struggle to survive in during winter in what is one of the coldest areas of Scotland. Granny’s children – my dad, aunty and uncle – spent childhood holidays on the old croft and retained strong attachment to the area. My husband and I climbed up Morrone one fine summer’s day and were astonished to discover my dad who had driven out to Braemar with us, and was then about seventy and in poor health, struggling up behind us. He made it up that purple remembered hill he’d scampered over all those decades earlier – made it up one last time.

The Tomintoul crofters were poor folk so that everyone had to do their bit. The young tended to go into service – girls became cooks or house servants while boys found work on the big estates of Balmoral and Invercauld or went into a trade. When no local jobs were available the connections made through these landed estates opened up jobs elsewhere in the UK. Granny became a cook to a wealthy London family and on her return to Scotland she cooked for a family in Stonehaven. One of her older sisters, Hellen, became the lifelong companion of ‘a lady’, a Miss Poole from Shepton Mallet, and the two young women travelled extensively abroad and in the UK. When Miss Poole died, as an old woman, the also elderly Hellen returned to Scotland, to Aberdeen near to Granny and the rest of her family.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. First there were two world wars to contend with. My grandfather, Granny’s young husband, joined the Royal Army Medical Corps (I have his notebooks from that time in which he scribbled down treatments for everything from shell shock to chilblains along with his wallet containing baby teeth from his children back home). I can only imagine the anxiety Granny suffered during the long years of the Great War guessing what her husband was enduring for he was a stretcher bearer in some of the worst fighting at the Battle of the Somme. But he survived it all. They lived in a tiny tenement flat in Skene Street in Aberdeen until the 1930s when bungalows were built on the west side of the town, off Mid-Stocket Road. It’s a mystery how they afforded to buy one but buy one they did and it remained in the family for over seventy years, nearly unchanged in all that time. It is in this house that I remember the only word spoken by Granny – whenever we arrived on holiday (when I was a bairn) she would pick me up to gauge how much heavier I’d got since our last meeting and call me Tina. I was Tina to no-one else but her. One word isn’t much of a vocal memory but there is a phrase that became something of a family legend though I can’t claim to have heard Granny speak it since I hadn’t then been born. It was during World War 2 when Granny expressed her resistance to the Nazis as the German Luftwaffe flew over Aberdeen dropping their bombs on the city, she’d be out the backdoor shaking a fist at them and shouting defiantly,

“Awa ye buggers!”

I think I take after Granny. Now I can’t claim to have heard her then but I recognise that spirit that stayed with her through her latter years. I don’t know what else Granny was doing through the war while her sons were abroad on military service and her daughter fulfilling her civic duty alerting Aberdonians to air raids but she appears to have made a point of stocking up on food for more than thirty years after her death we found tins of wartime food stored in her cellar. Unopened.

Unusually, my grandmother was ten years older than her husband, my Granda, and considerably taller, but for all their unconventionality theirs was a long, and as far as I am aware, a happy marriage that began in 1911 when my grandfather returned from a spell working in New York to marry his Hetty. He was 21 and she 31 and they had met when he was working as a young baker in Braemar.

Granny was a woman of her time – such a silly phrase as everyone is. She wore her skirts long, often to her ankles, over red flannel petticoats. The beautiful costumes I found in her wardrobe may not have been hers but her sister Hellen’s (though I don’t know for sure).

It is a pity photographs are silent. Sometimes it is a pity. Granny’s voice will always remain in my imagination, an odd word captured in a rather high-pitched, thin, reedy tone and a smile behind each one. If only I could capture more of them.

***

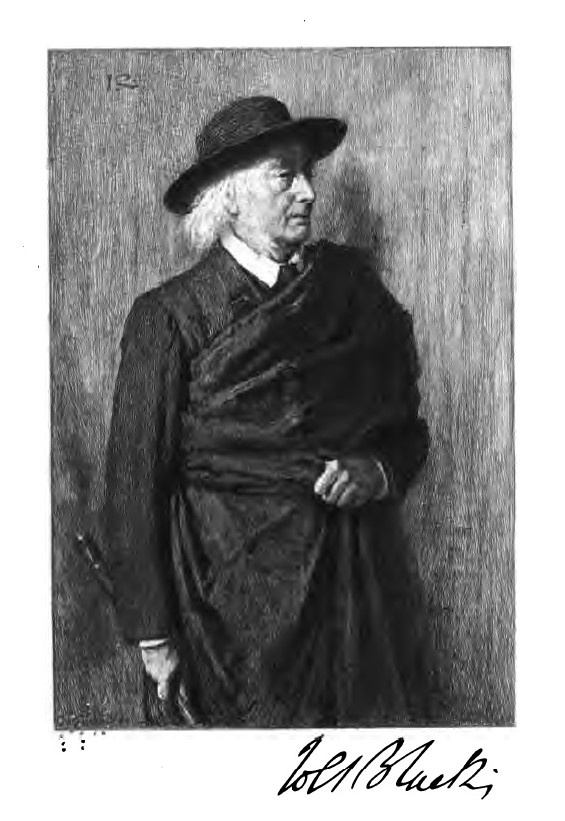

My other granny, my maternal granny (Granny 2), has also been more or less silenced since death. She was about ten years younger than Granny 1 and was also a daughter of a crofting family but hers lived in the Black Isle which enjoys one of the mildest climates in Scotland. A Highlander from Cromarty, Granny 2 was Isabella (Bella), a Miller (sometimes Millar) whose extended family included the geologist Hugh Miller. Like Granny I, Granny 2 was tallish but otherwise they were very different types of women. For one thing, Granny 2 would never have thought of much less uttered Granny 1’s immortal commands to the Luftwaffe.

While not being able to very clearly recall Granny 2’s voice I should because when she was old and had succembed to dementia she would near-endlessly recite rhymes remembered from her childhood or those she shared with her own children. “Here we go round the mulberry bush was often shortened to “on a cold a frosty morning” recited with gusto, as our daughter remembers. “Losh, losh” she’d repeat over and over again – losh being a Scots word for surprise though Granny didn’t say it with any sense of its meaning but more a lament, for what I can only wonder. It was a sad end to her life, drawn out over many years – she seated day-long with nothing to occupy her mind and slipping inevitably into a world of her own, living with her family but separately.

I imagine because I wasn’t there the night she called out in her sleep for her recently dead husband – “John!” was uttered urgently but softly in that light way people with the Gaelic have of talking with a soft palate so that words trickle from the front of the mouth. Bella’s vocabulary was well sprinkled with the Gaelic though she disdained Scots for her generation were encouraged to be ashamed of their own traditional language. A generation before young Bella was born her family were cleared (a polite term for being driven off their land) from Strathconon and ended up in the Black Isle and it was instilled into the people that progress equalled English and backwardness equalled Scots. So Bella venerated the English language and I recall her urging me to say ‘yes’ instead of ‘aye’ – but I cannot remember how she said it.

For all that she was a kind and gentle woman, more stoic than her appearance might suggest, encouraging her young farmer husband to take the plunge and rent a bigger farm and in time buy it. They were a team. In common with all farmers’ wives, Bella was responsible for some farm work as well as her domestic duties – eggs and dairy products which she sold at markets each week loading loading eggs, cheese, butter and cream onto the trap and driving the horse the twenty or so miles to Inverness for the weekly market – and presumably Dingwall and Muir of Ord, too.

She and my grandfather married in 1912. Like my Aberdeen grandparents they were 21 and 31 but unlike them the bride was younger than her husband. Unlike Harriet’s husband, Bella’s man was not active abroad during the Great War as farming was a reserved occupation and he had carried out pre-war training in England when he was introduced to the joys of motorcycling but couldn’t work out how to stop his bike so drove round and round the compound until it ran out of fuel. Family members who were at the front included Granny’s cousin whose letters from the trenches are shown here. Many Scottish women were forced to give up their jobs to travel to England to manufacture munitions during the Great War. Bella’s sister, Anne, was one of them conscripted by the government but she was allowed home towards the end of the war to take care of Bella and her children who were suffering from the deadly Spanish ‘flu of 1918. They all survived.

Bella had a passion for auctions or maybe it was a passion driven by necessity. She and John moved into their final home and farm near Strathpeffer in the 1920s and the rambling old farmhouse took a lot of filling. Bella furnished it with all sorts of weird and wonderful pieces purchased from the Dingwall mart, including a large glass display case of stuffed birds I spent so much time staring at as a young child. The house was a magical playground for us children with more than fourteen rooms plus bathrooms. There was a pantry where Granny’s home-made jams, jellies, chutneys and wine (lethal) were stored, a laundry with an enormous timber sink and a dairy where Granny turned the farm’s milk into the butter, cream and cheese she sold at markets. The dairy was always cold irrespective of the heat outside for it was built as a short wing lit by a series of small windows along a single wall shielded from direct sunlight. A row of meat safes and metal presses sat on long wide shelves to keep food cool and insect free. A large room with ample space for food on one side while the other was stacked with decades worth of Ross-shire Journals and editions of the Scotsman. And now I cannot access Ross-shires of that time. I could write a whole blog on the different rooms, some grand and others basic and functional but the lovely building that was always open house to so many in the area, friends, family, visitors and strangers alike was mysteriously destroyed by fire shortly after the farm was sold.

Bella was said to have had the second sight, based on a single incident I believe. The second sight is a phenomenon some believe occurs when someone ‘sees’ an event happening either in some distant place or in the future. In Granny’s case her experience came during World War Two. Her young son who’d lied about his age to join the army disappeared in North Africa after his tank was destroyed. The family didn’t know if he was alive or dead. One morning Bella confidently announced that he was safe for she had dreamt of her son as a baby in a cradle that rocked back and fore, quicker and quicker, until it slowed to a stop. Her confidence was well-founded and her son did eventually return home after four years as a prisoner in Nazi labour camps in Germany and Poland.

Both Bella and Hetty grew up at a time shanks’ pony was the most common means of getting around and horse and trap for longer journeys. They lived into the age of motor cars and motor cycles, the replacement of paraffin and town gas with electricity, from a world in which correspondence meant letters and telegrams to one with near instantaneous communication, the wireless and telephone and eventually television. They lived through a century of incredible societal changes. Of devastating world wars and numerous other wars and conflicts and the crumbling of the British empire. It would be wonderful to be able to sit down and talk to them both about the world’s momentous events and little domestic dramas but that’s just idle contemplation. Now it is easy to record grannies in full flow so their voices can accompany those who care about them into the future and that can only be a good thing.