War in the Western Desert was not going well for Britain with Rommel’s tank corps making steady headway. At the end of May a fresh German offensive broke through the British defensive line forcing the British back to Egypt.

Back on the farm 69 acres were put under oats, 30 with barley, 10 with potatoes (Kerr’s Pinks and Redskin), 24 with turnips, 61 acres were sown as meadows and 120 left under grass and so on. John’s sister, Margaret, was again helping occasionally such as at tattie lifting in October, alongside school children on their tattie holidays. Tattie picking holidays were established in Scotland in the 1930s to provide extra labour to gather-in potato crops in autumn and came into their own during the war when labour was in short supply and picking up tatties didn’t take skill, only energy. During wartime shortages of experienced farm workers created a few headaches because the production of food was essential not only for the domestic market but to provide for military personnel overseas. Men’s wages were increased in January of 1942 from 48 shilling per week to 60 shillings. Women were always paid less irrespective of their skills. With so many men on military service women were recruited as the Women’s Land Army, their deployment falling under the Secretary of State for Scotland.

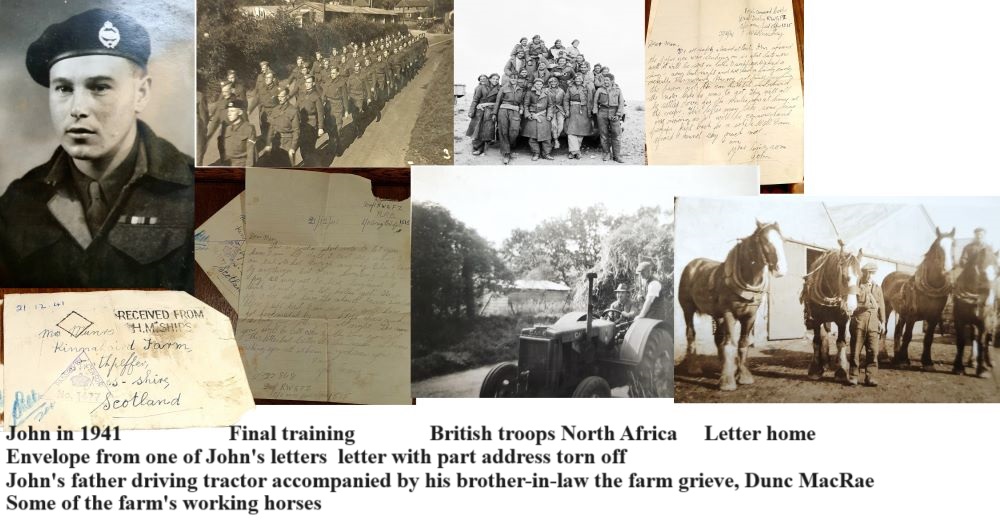

On January 3 John’s thoughts were very much on the Scottish Hogmanay and his aunt and uncle from Inverness who visited at the beginning of each new year. Then a little over a week later John’s mother, Bella, is sent a letter written in a beautiful hand from Seaforth Avenue, Durban, Natal, South Africa.

“Dear Mrs Munro,

This is just a short letter to say that we had the pleasure of entertaining your son, John, during his short visit here. We took him and his two chums one from Dundee and one from Glasgow to see some of the sights near the town including the wild monkeys. Then we brought them home for supper and they spent the evening with us. The boys enjoyed their stay here and it was a nice break after their long voyage. They also tasted some of our fruits which they had never even heard of before. They all looked very fit and well and very brown. This is the first Scottish boys we have had and we enjoyed their company as we come from Perthshire.

We think it a great privilege to be able to do something for the boys as we are too old for military work so we do what we can in the hope that this letter will be some comfort to you.

Trusting that this will find you and your husband fit and well and that you will soon have your son home again. We are yours sincerely, Mr and Mrs J. Shephard.”

On the 30th of January 1942 John wrote home from his training base to reassure the family he was alright and getting settled in camp. He makes a guarded reference to his visit to Durban but not by name, to avoid the censor’s blue pencil –

“Did you get any letters from a town we touched on our way out. There was a couple there who took us around who said they would write home. They came from Scotland. This place is not very hot just now. It is just like summer at home but it is very cold at night. It is pretty dusty too and every step you take raises a cloud of it. Today was pay day and we got 100 piastres or ackers as they are called. It is equal to £1 but it does not stay as long as anything worth about 1d at home costs about an acker here. We get our washing washed and ironed for 3 ackers by the dobeys or something that sounds like that. There is a Church of Scotland canteen down the road called Scots corner. The funny thing about this money is that you have a pile of notes and it may not be worth 10/-. You get notes for 5 ackers worth about 1/-. When we were on the train coming here a swarm of hawkers came on and started selling a lot of trash bangles wallets etc. As there was no money among us they started to change them for old pens and odds and ends. I never changed anything as there was nothing worth buying. I would look very nice I daresay with a string of beads round my neck and a few bits of stuff round my wrists. Some of the rest of them changed stuff. They will be throwing it away yet likely enough. We get good enough grub and beds here but we have a few partners in the beds with us. The place is full of them. I hope everything is all right at home.”

1d is 1 penny and /- is the sign for shilling. He goes on to mention the family at home and complains at the time, sometimes months, it takes for mail to arrive. Finally there is a reference to the troops’ allocation of 50 cigarettes and extra 4d a day colonial allowance.

Between censorship, distance and sheer volume of military mail letters took on average three months to be delivered but telegrams were sometimes a possibility, albeit an expensive one. On 2nd February 1942 John sent a Via Imperial telegram to his mother.

“ALL WELL AND SAFE PLEASE DONT WORRY KEEP SMILING.”

This was followed up five days later by a brief pencil-written letter informing the family of his new address – B. Squadron, 3 R.T.R., M.E.F. (Middle East Forces). He expresses relief having at last joined a battalion for he was fed up of the –

“…spit and polish at the Fort but in a battalion they have a bit more sense…It seems funny to be in the middle of winter and the sun shining every day. It is a bit cold at nights though.”

While this letter was written in February, he realised his mother would not receive it until the summer.

On 14 February John sent home an airgraph, a type of telegram that photographed letters in miniature and sent them on by airmail. He was again frustrated at not receiving mail and it’s clear he was thinking a great deal about the family at home in Scotland. He drew the letter to a close as the last post was being sounded asking his teenage brother Roy if he has been busy keeping down the rabbit population on the farm. Rabbits were often shot but they were also trapped with snares.

“This is not the sort of country to be in to be setting traps in here. You would need to watch them 24 hours per day. They would pinch the colour from your shirt and swear down your throat it was white. There is a lot of dud coins too. If you give them a five acker piece or upwards they will ring it on a stone and as like as not refuse it. After a few days you do the same yourself or if not you will have a pocketful of useless stuff on you. I got rid of all my duds so just now I am all right (I hope). They pester you all over the place in town trying to brush your boots or sell you something. You get a real good feed here though. Plenty of eggs. 4 eggs and chips tea and bread and salad and what not for about a bob (or five and six ackers). Well Roy that’s lights out so I will close . . . I saw a right good acrobatic turn the other night. It would beat anything Bertram Mills circus ever had. Well Roy, cheerio, I am your loving brother, John.”

On 10th March 1942 he wrote to say he had received a letter from his Mam, his mind is on what was happening with the routine seasonal work on the farm such as spring sowing and describes a little of his impressions of agriculture in the middle east –

“You should see them pumping water out here for the fields, you should get Roy busy with a pump if you get a dry year … I was pretty lucky I came here according to the newspapers as the other places do not seem so healthy the last few months.”

In addition to his usual interest in what the family are up to he mentions a picture card he’d sent home, possibly of Durban, and makes a reference to a sea journey, likely from South Africa to North Africa with his tank regiment.

“I was not seasick although the most of them was in a bad state for a few days.”

He regrets never receiving local newspapers sent to him by his mother and urges her to forward the Ross-shire Journal, closing by asking if anyone else at home has been called up.

“I think I had better close as I am going down to get my tea. I am your loving son, John.”

On 24 March John again complains that so few letters sent to him from home are getting through to him. You can be sure his close-knit family were writing and problems with the mail system were at fault. His mood is low and he has little to say aside from a mention of dust storms in the area. However, days later, on the 29 March his mood has lifted. Those longed-for letters and a telegram from home have finally arrived. Three of those letters had been posted from Scotland in December of the previous year and another, from his sister Margaret, sent on 1 January 1942. On receiving them John immediately wrote back. Life in the unit was monotonous he indicates and it appears he is lonely; complaining of not seeing anyone he knows or even any fellow Scots despite Scots being in the vicinity. He refers to the weather, already hot, is growing hotter and how hot it was on the boat (north from South Africa) and his sunburn.

“It was so hot that a lot of us got our hair all cut off. We looked like a bunch of convicts but it is a fair size again. What I am wondering now is whether I will part it or just let it grow. I think I will have it without a parting as I have got my combe broken and I did not have the chance to get another. I was wondering if I could manage to make one out of a petrol tin but I gave it up. Still I’ll get one soon I hope.”

Looking good was still a priority despite the privations of life in the Western Desert.

Those local newspapers he longed for eventually arrived, or rather clippings from them – the Bulletin I’m not familiar with and the North Star I think was The North Star and Farmers’ Chronicle. He writes about how much he’s missing news of home and is longing to read about what’s happening there, again requesting his family send him copies of the Ross-Shire Journal even though they’ll be six or eight months out of date by the time he eventually gets to read them.

3rd April 1942. In a letter to his mother John’s mood is again flat and he has little to say. He’s in north Africa and suffering in the heat. There’s a mention of getting his RAC beret (which he wore all his days while working on farming after the war) and going off to the pictures “in a whilie” within the camp as they aren’t allowed out.

“We handed in our kitbags today to go away and we will get paid today. I have the new address but it is only after embarkation. You had better hang on for a day or two before you write. Well that’s all, I am your loving son, John.”

If only we had his mother’s letters to him. Sadly, none have survived.

Back at home newspapers were full of the war in the desert and the struggle against Rommel’s forces. Young John was a tank commander in the thick of the action that involved hundreds of jousting tanks and continual whizzing and cracking of exploding shells that left spirals of white smoke hurtling skyward and explosions of flames as tanks were hit and caught fire. Visibility was cloaked with clouds of desert sand and thick acrid oil vapour from blazing tanks. The clamour was deafening.

29 April 1942. John receives an airmail letter from home that took only a fortnight to arrive. Surface mail was still taking around three months. He writes back –

“Things seem to be wakening up a bit at home according to the odd scraps of news we get now and again.”

He’s referring to Luftwaffe and RAF bombing raids of Britain and the Continent.

“I heard they had a pretty strong raid on France too not so long ago. I hope they make a right strong one by the time this letter gets to you and stay there. We ought to be pretty well equipped all over after nearly three years of preparation. The air force seems to be by the look of it and the army is not much good without air support. The Russians are still doing fairly well I think. Well they can afford to lose plenty of men. They have plenty to draw on. At present I am along with a lot of Englishmen. Some of them are all right but some are not. The best lot I came across were the ones I trained with who came from infantry regiments. The RAC ones have a lot of well to do ones – civil servants and so on and I don’t fancy them. There is one with me now who talks lah-de-dah like a toff. He thinks and always likes to tell everybody who have no other option but to listen that Churchill has never done anything worthwhile since he became prime minister. He calls himself a communist but hasn’t the brain to be anything other than a windbag. He has had a pretty easy time by the look of it. A good walloping would do him the world of good. Of course they aren’t all like that but there are quite a lot of them I dislike and despise. One of the blokes from the Seaforths (there are only three of us here now) is fed up with them too. He is on a lorry with other two. The Gerry used to say the English man was decadent. A lot of them are. In another twenty years or so by the look of the better class it may be the best of the whole lot are the ordinary working man.”

He’s again frustrated by the army censoring so much of what he wants to write but understands it’s concern that letters will fall into Gerry’s hands, revealing military positions. He asks about home and mentions that he recently wrote to his Granny (like most of the letters this one has not survived). Again the hot African weather is mentioned necessitating them changing into shorts instead of the battledress they had been in on landing in the cool season.

“I don’t think they have the right idea of the east at home. It’s a lot different from what is talked about it – waving palms and all the rest – there are some but the most of the waving palms belong to the nippers shouting ‘“Baksheesh George. Give it”’ they are always trying to cadge something off you, money or cigarettes. They are awful bargainers too. I bought a wallet with stamped leather designs from one of the kids. He wanted 15 ackers for it about three bob. I offered two. He muttered something in Arabic and came down to 10. I offered three and he came down to eight at last I got it for four and a cigarette. The whole deal took about half an hour and I still think I was robbed.”

The 8th Army had nearly 850 tanks in the region, nearly 200 planes and 100,000 men protected by the Gazala Line – a huge minefield that extended for 43 miles inland from the coast. John’s 3rd battalion were involved in the near non-stop action. Assumptions were made by the British command about German tactics. They got it wrong. Rommel launched an attack on 26 May 1942 (John’s sister Margaret’s 26th birthday). Both sides struggled with inadequate supplies for their troops but Germany’s tanks and air defences proved superior to those of the British and Rommel’s Panzer division pressed forward finally penetrating British positions and securing supply lines to consolidate German’s grip on the region. A British counter attack was launched on the 1st and 2nd of June amidst severe desert sand storms but the British action was repulsed by the Germans resulting in the destruction of many tanks, their crews killed, injured or captured as POWs. On 5th June Operation Aberdeen went badly wrong with vast losses of British troops and equipment and thousands of men captured.

The war in the desert was reported back in Britain but perhaps not in a way that was recognisable to the men involved. The 4 June edition of Aberdeen Evening Express was upbeat about the progress of the Allies campaign –

“…we have been able to cut off the head of Rommel’s forward positions… at last light on June 2 our armoured forces drove the enemy out of Tamar… The enemy are known to have lost at least fourteen tanks in this engagement.”

No mention of Allied tank losses which were huge. And on 11 June 1942 the same newspaper had this to say –

“…there are many more around who, though not yet shouting, are supremely confident of the final result.”

On 16th June optimistic propaganda exploded into bombastic hyperbole with embedded war correspondents describing British convoy commanders

“…sitting up aloft on their trucks like sunburned gods – their sun compasses pointing a black sliver of shadow towards the Boche”

Aberdeen Press and Journal 16 June.

Towards the end of the month the British press was still painting a positive picture of the desert campaign –

“It is these battle groups which are enabling strong British forces to operate with deadly effect well behind the Axis lines.”

With the surrender of tens of thousands of British-led troops to the Axis powers, Churchill later wrote

“Defeat is one thing. Disgrace is another.”

Back on the farm it was a bumper summer for barley and oats but unfortunately much of the crops had to be left in the ground because of a scarcity of sacks and transport.

On 14 July 1942 a generic statement was issued to John’s father at the farm from the Cavalry and Royal Armoured Corps. It was misaddressed but he eventually received it.

“I regret to inform you that a report has been received from the War Office to the effect that (No.) ******* (Rank) TPR

(Name) Munro J.

(Regiment) 3rd Btn. Royal Tank Regiment was posted as “missing” on the 2nd June 1942 in the Middle East.

The report that he is missing does not necessarily mean that he has been killed, as he may be a prisoner of war or temporarily separated from his regiment.

Official reports that men are prisoners of war take some time to reach this country, and if he has been captured by the enemy it is probable that unofficial news will reach you first. In that case I am to ask you to forward any postcard or letter received at once to this Office, and it will be returned to you as soon as possible.”

John’s disappearance was one of many reported in the press during July 1942 –

“Mr John Munro, farmer, Kinnahaird, Strathpeffer has been officially informed that his son Pte. John Munro R.T.C, is missing.”

The news would have been a devastating blow to the family, one shared by so many in Scotland and countries everywhere. John’s mother must have been beside herself with grief and worry but then one morning she announced to the family “John is safe” for she had dreamt in the night of a baby in a cradle furiously rocking back and fore before slowly steadying and coming to a stop which she interpreted as her son John as the baby in the endangered cradle that stilled with the child safe. She wasn’t to know then but John was the sole survivor of a tank destroyed in battle.

On 2nd August 1942 a plain postcard was written by John.

“Dear Mam,

I hope you have not had long to wait to learn I was (a) prisoner. You do not need to worry about me. When you reply write c/o Italian Red Cross, Rome. Well I will close now. I am your loving son, John. “

John and his fellow captives from North Africa were transferred to Sicily’s Camp PG 98 Prigione di Guerra (Prison of War) under a prisoner agreement between the two fascist governments of Germany and Italy. Prisoners were stripped, deloused, their heads shaved then allocated a tent with about fifty others. The camp in a mountainous area was cold, wet and windy and difficult to escape from. Food consisted of tiny rations of bread, cheese, pasta or rice at best -a handful of berries at worst. There were high levels of sickness, diarrhoea, dysentery and vomiting due to the filthy conditions and near starvation rations. I don’t know if John tried to escape while in Italy. He did break out of camps on several occasions, possibly in Germany where in the earlier stages of the war failed escapees were questioned and returned to camp and perhaps put in solitary confinement for a few days (towards the end of the war they were often shot dead), but in Italy a recaptured POW might be tethered to a flagpole and left for days without food. For many of the very sick Italy was the end of their journey. Surviving POWs such as John were further transferred into Germany. There camps were well protected with trip wires around the perimeter and backed by double barbed wire fences topped with coiled barbed wire, perimeter towers with armed guards and regular foot patrols of camp guards.

There were short rations, too, for farm stock back in Scotland because so little winter feeding was available. Less fertile land was ploughed as an attempt to grow more food instead of relying on foreign imports that tied up vessels and cost mariners’ lives.